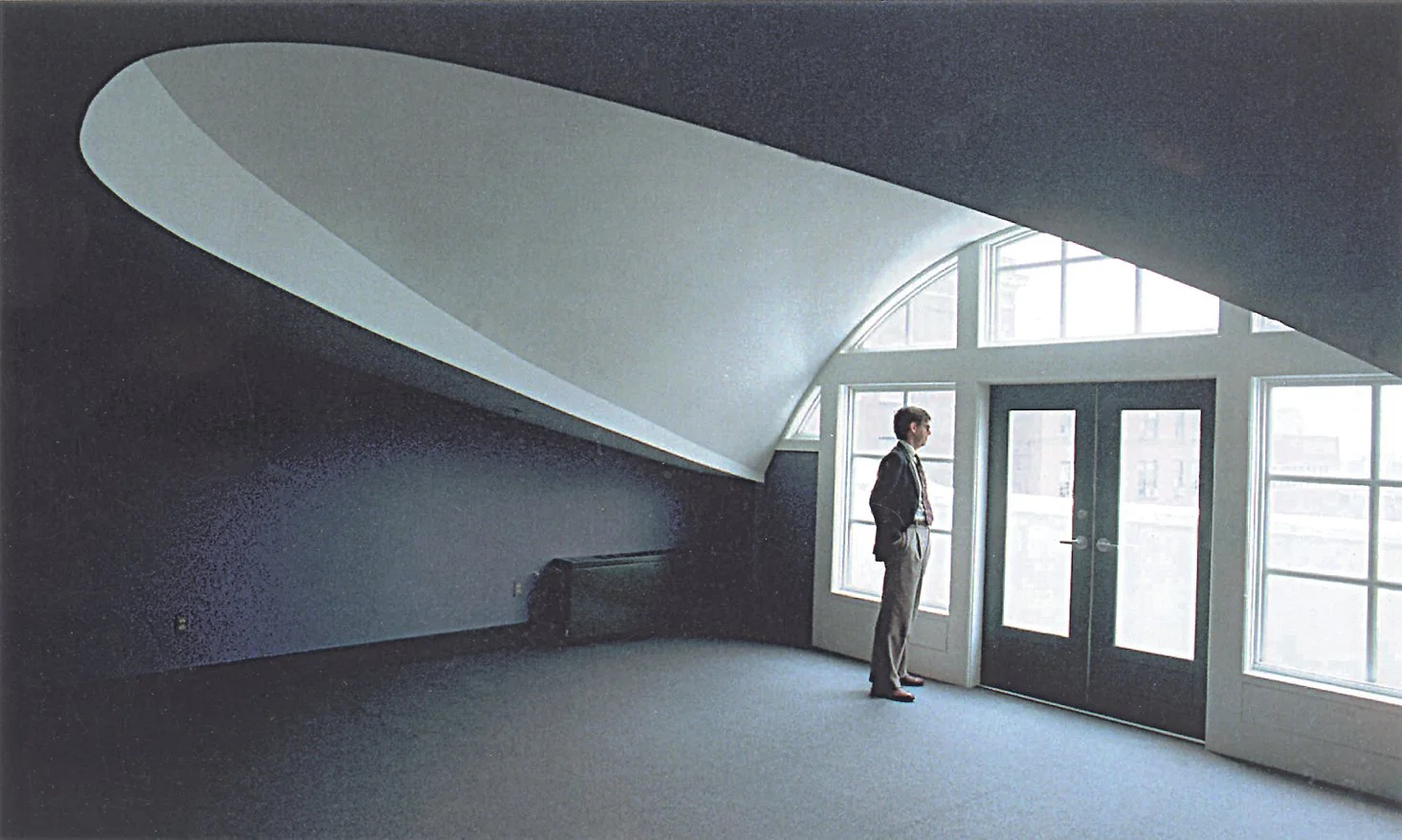

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects re-made the Baltimore courtrooms to create the proper atmosphere of tranquility and fairness in the space.

Going to court – whether as a plaintiff, defendant, or juror – is rarely a pleasurable experience, but the right setting can help deliver a feeling of tranquility, fairness, and even pride in one’s community.

“These courtrooms absolutely add to the sense that justice will be done here,” says Peter Schwab, AIA of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, discussing the new courtrooms M&D designed for the historic Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr., Courthouse in downtown Baltimore.

Built in the late 1890s, the impressive building, named for the Baltimore lawyer and national civil rights leader, is the main building in the Baltimore City Circuit Court complex.

Like us on Facebook!

The structure contains marble facades, staircases, and columns, along with mosaic tiled floors, mahogany paneling, beautiful murals, and domed skylights.

Inside, though, not all of it was so majestic.

“The third and fourth floors were renovated in the 1950s, from what were open courtyards on the interior of the building into office space,” Schwab says. “It was a mess and kind of depressing.”

It didn’t reflect the rest of the building, the gravity of what happens here, or what Schwab feels the community wants representing it.

Providing dignity

Because this office space didn’t have the historical value of much of the rest of the building, M&D was free to re-make the courtrooms to create the proper atmosphere.

“We created contemporary courtrooms with LED lighting, direct and indirect, both up and down lighting, rather than the straight down lights that were there,” Schwab says. “Up and down lighting is important in courtrooms because you want to be able to see people’s faces. With straight down lighting, that’s harder,” he explains.

In corridors where the building’s history lives, M&D chose rift cut oak.

“The log is sliced in the middle, perpendicular to the grain, giving it a more parallel look,” Schwab says. “We coordinated this with the judges’ and juries’ benches, which were purchased separately.”

The firm also matched the stain colors of the veneers with woodworking on the walls – including wood cornices – and the judges’ benches and jury boxes.

“These rooms now have the proper ‘institutional quality,’” he says, “which is not usually thought of in a good way but is in this case.”

Challenging work

The renovations were done in a working courthouse, meaning much of the heavy, noisy work had to be done overnight. Because of the historical nature of the staircases and corridors, including marble from the Vatican Quarry in Rome with carvings that took years, equipment had to be taken up in elevators.

A huge air handling unit had to be broken down, taken up in the elevator, then re-assembled, Schwab recalls.

“There are very nice, heavy, 8-foot wooden doors from the original building, which we had to re-finish on site,” he says of another challenge.

Architects also found an enormous steel beam, originally outside in the exposed courtyard, inside a wall where a courtroom entrance was planned.

“We had to be flexible working with the existing conditions,” Schwab says.

19th and 21st centuries meet

While the building is historical, the courtrooms need to function in today’s world. To accomplish this, M&D got courthouse workers involved.

“We coordinated with judicial information systems in Annapolis,” Schwab says. “We put in new IT systems, coordinating the judges’ benches with administrative assistant areas.”

There are also microphones built into judges’ benches and ADA ramps to the benches and elsewhere in what Schwab describes as “meticulously laid out courtrooms.”

Security cameras and other safety measures are incorporated into all areas, including judicial chambers, jury rooms, and courtrooms.

A better space for all

“The judges are thrilled with the re-invention of the space,” Schwab says. “But, we thought about the other people involved in courtrooms, too. Juries are important, as is the work they do here.”

Schwab thinks the building better represents the ideal of justice in the city and projects a better image to all who come here, be they jurors, plaintiffs, defendants or those supporting people involved in the proceedings.

“Now, when you go into the courtroom, you just feel better walking in,” Schwab says. “I believe more people come out thinking it was a positive experience.”

To round out our 40th-year celebrations, enjoy 10 more impactful and diverse Architecture projects designed by M&D. These projects, most of which have received design awards, confirm the variety in design (from scale to usage) that we continue to be involved in today.