Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects’ work on the new Victory Villa Elementary School also met silver LEED certification requirements.

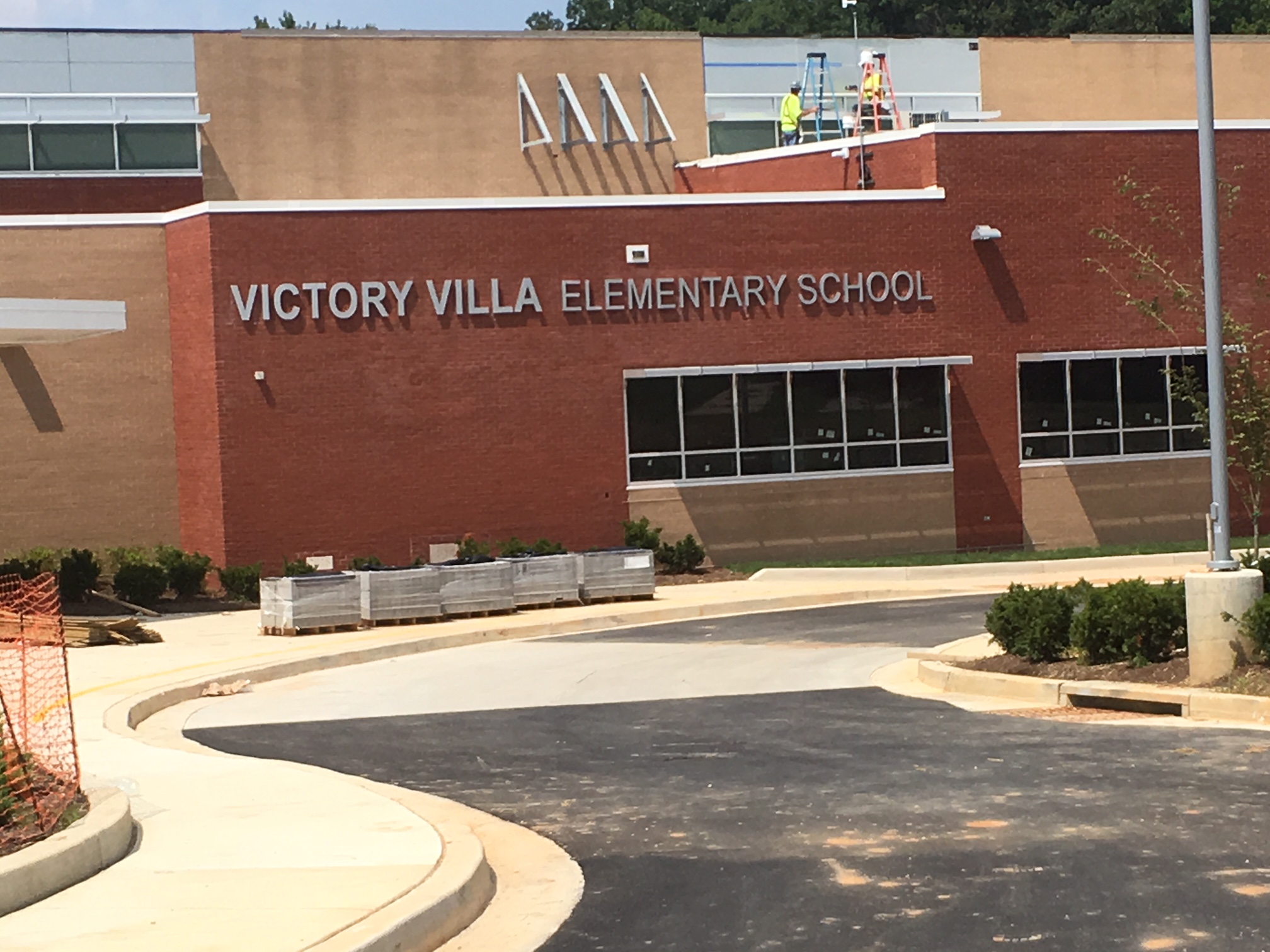

When 735 students returned to Victory Villa Elementary School in northeast Baltimore on Sept. 5, they entered a new 75,000-square-foot hall of learning that is outfitted for the future.

But without the inclusion of a special exhibit to salute the school’s historic past, the structure could not have been built.

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects of Baltimore and York, Pennsylvania, designed the building on a physically challenging site to replace a wood-frame school intended to be temporary but which served students for 76 years.

The new school features energy-efficient mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, building materials with a high recycle content, and a “green” instructional roof with planters, a weather station and a solar-generation demonstration facility.

The school was designed to meet the criteria for silver certification from the federal Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program (LEED).

Considering scale

The site is compact, creating one of the challenges that faced architect Lauren Myatt, the lead designer on the project.

“We created a two-story building that also had to consider the proportion of the rest of the neighborhood,” Myatt explains. “When houses and the community sprung up in the 1940s, most houses were bungalow homes.”

To avoid overwhelming the houses closest to the campus, the new school tapers to one story on its east and west ends. The front entrance also is scaled to one floor. The exterior has two shades of brick, so the building doesn’t seem as massive.

The original one-story school was erected in 1942 to educate the children of World War II defense workers at the Glenn L. Martin Co. aircraft plant in nearby Middle River. The factory built thousands of B-26 Marauder bombers from 1941-45.

“That plant was thrown up rather quickly, and the town around it to house workers,” explains architect Bruce Johnson, who worked on the design and oversaw construction of the new school. “And, of course, in conjunction with that they needed a school and community activity center.”

To shield the defense operation from enemy eyes, the factory was made to virtually vanish by the 603rd Camouflage Engineer Battalion, appearing from the air to be verdant countryside, according to the documentary “The Ghost Army.”

Dealing with rainfall

Space for the new school was tight because much of the lot couldn’t accommodate any new construction.

“The site itself is just over 12.5 acres. Nearly two-thirds of it is located within the 100-year floodplain, which makes it an unbuildable area without going through extensive site design measures,” Myatt says.

So, the new school was designed to occupy the same general footprint as the old school, outside the floodplain.

Storm-water management needed to be addressed. With the summer’s relentless rain, Johnson says, the architects saw the potential problems for the property.

“There are a variety of storm-water management facilities on the site, including retention ponds and underground storage tanks that handle storm water compactly,” Myatt says.

Recognizing history

A few design touches were salvaged from the original building.

“The old school had a lot of tongue-and-groove maple flooring throughout the main corridor,” Johnson says. “We used the wood flooring material on some focus walls in the main lobby space and to form a bench area going to the second floor.”

Also in the lobby is a display that highlights the history of Victory Villa. Though a new school was needed, it could not have been erected without that exhibit.

Because the old wartime school was considered historic and because schools receive state funding, Baltimore County Public Schools needed the approval of the Maryland Historic Trust to replace it with a new school, Myatt says.

Like us on Facebook!

The display in the lobby satisfies the required nod to history.

Murphy & Dittenhafer worked with a committee of school system and school personnel and the consulting firm Adler Display to create the exhibit, which focuses on student activities and the original building.

“Items in the display include some old wooden toy airplanes,” Johnson says. “There is a drum from the old elementary school band. A lot of information in the display is narrative, and there are photos of classes from back in the ’40s.”

In another tip of the hat to history, the new school has two cornerstones. One reads “2018,” the other “1942.”

With an assist from Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, Victory Villa students, who live on streets with names such as Compass Road, Propeller Drive, and Fuselage Avenue, will enjoy the benefits of a high-tech school that has not forgotten its significant history.

Harford Community College’s expanded new construction Chesapeake Welcome Center is a lesson in Architectural identity